Biography

Early Years

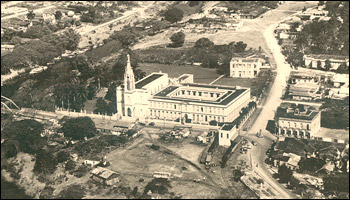

I was born in Havana, Cuba, and grew up some distance east of that city, in the small town of Sagua la Grande. I was fortunate to be part of an extremely musical family. My father had trained as an opera singer and my mother was a marvelous pianist. My earliest memories include music in every imaginable familial environment. From infancy, tucked in bed in the evening, my brothers and I heard piano works of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, Brahms and many others. As we grew older, requests for personal favorites could be heard out of different bedrooms, which my mother would grant from her piano parlor. On specific days we would gather in my father's music room to listen to recordings. His collection included some of the most enduring works in the symphonic literature. My brothers and I thought all of this to be entirely a routine matter. In spite of the fact that only I turned out to be a professional musician, to this day my brothers enjoy good music as an indispensable component of their everyday lives.

Of course, everyone in our family studied music. The learning followed traditional guidelines: piano was the fundamental instrument; music theory, history and literature were essential matters. Our extended family valued music highly too. Several of my aunts had studied classical guitar from the time they were very young. When we spent holiday time together, there were always several guitars on hand for accompaniment of songs, as well as for solo playing. I vividly remember the allure of even the simplest sound of a guitar on a quiet moment. For me, it invited private times and introspection—and conspiracy. By then I was studying violin and the guitar was all the more attractive in that it allowed a personal expression unrelated, I thought, to the rigors of the rest of my musical studies. It wasn't long before I discovered that the serious study of the guitar would be as rigorous as that of other instruments to which I could relate. Furthermore, my studies of piano, violin, music theory and literature were directly applicable in important ways to the study of the guitar. And so it began for me.

All the while, music was studied and made entirely for the enjoyment of it. Cuba was not a country where musicians were well remunerated, save for the popular idols. My parents wished for my brothers and me professions of more promising future. In 1959 the political and social situation in Cuba changed dramatically. A year later, under threatening circumstances, my parents decided that we should leave Cuba for the United States and request political asylum in this country. The circumstances of our exile from Cuba and the events of the ensuing years were pivotal for us.

Transition

Settled in a small apartment, in a new city in a foreign country, life took a turn for everyone in our family. I became involved with a group of Cuban dissidents. We landed in Cuba, engaged in armed conflict and were defeated. Many of the survivors, including myself, ended up as political prisoners in Cuba. Our prison was an old castle built by the Spanish during the time of the colony. In those centuries-old dungeons, the combination of uncertainty and boredom was a disastrous mix that afflicted many. There, just past my nineteenth birthday, I became fully aware of the power that music had for me, aware of what music could do for me when everything else failed. I was able to understand that I would need that sustenance and refuge many times again in my life. That is when, and how, I came to the decision to devote my efforts to music as a lifelong profession. Of course, it would only happen if we could ever get out of the dreadful predicament in which we found ourselves.

Our release was negotiated after nearly a couple of years. Back in the United States, I had the opportunity to take a college degree in musical performance under Héctor García—my teacher, friend and fellow political prisoner in Cuba. A graduate degree in guitar performance was a possibility very few schools in the country offered at that time. Master classes with distinguished artists were much less frequently available in those days than they are today.  I was fortunate to attend a summer class with Julian Bream. From that wonderful master I learned much then, and have continued to learn over the years. I remained intent on pursuing a program that would give me a broad knowledge base from which my musical judgement would gain insight and academic weight, qualities which at that time guitarists were thought, mostly by academicians, not to have. Since very early on I had a serious interest in writing—transcribing and arranging, which I saw as a form of composition—and a personal enjoyment of musical syntax. So it was that I chose music theory, the theory of musical performance, as my graduate focus of attention. After completing a Ph.D. in music theory at The Florida State University, School of Music and gaining the valuable experience of teaching and developing a guitar program at that institution, I assumed an editor's position with a music-publishing firm.

I was fortunate to attend a summer class with Julian Bream. From that wonderful master I learned much then, and have continued to learn over the years. I remained intent on pursuing a program that would give me a broad knowledge base from which my musical judgement would gain insight and academic weight, qualities which at that time guitarists were thought, mostly by academicians, not to have. Since very early on I had a serious interest in writing—transcribing and arranging, which I saw as a form of composition—and a personal enjoyment of musical syntax. So it was that I chose music theory, the theory of musical performance, as my graduate focus of attention. After completing a Ph.D. in music theory at The Florida State University, School of Music and gaining the valuable experience of teaching and developing a guitar program at that institution, I assumed an editor's position with a music-publishing firm.

Later Years

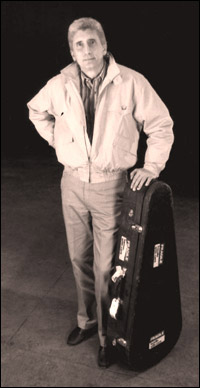

By that time I had written several arrangements and transcriptions for guitar, ranging from movie themes to lute music of the Renaissance. Hansen Publications Inc. produced and distributed those widely, in the U.S. and many other countries. When I joined them as editor in 1972, I envisioned an opportunity not only to produce guitar music for publication, but perhaps also to write for orchestral ensembles, do some studio work and get out to do a recital or a concerto now and then. I found out that Industry was not a good base of operations for what I had in mind. A year later, I accepted a position on the faculty of The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Department of Music, where I found competent artists, teachers and researchers among my colleagues, and a warm community of wonderful environs. I have remained on the faculty of this institution until the present time. I have a guitar studio class of talented and interested young guitarists and teach graduate courses in music theory, musical styles and orchestration. Over the years, I was fortunate to be able to travel for recital and concerto appearances throughout much of this country and beyond. It was a special experience to visit and play in the Dominican Republic, an island-country very near to, and very much like Cuba. I have been able to return there several times and develop lasting friendships and a warm fondness for that beautiful country.

Until the early 1980s I continued writing guitar music for publication by Hansen House and, a few years later, by Columbia Pictures/Belwin Mills. Much of that work is no longer in print. In my experience, writing for a publisher of music sometimes imposes serious limitations of conception and scope on the writer. Quite a few of my arrangements and transcriptions—a number of my favorites—were never published. Often they would not suit the publisher's needs to produce collections of certain specific kinds: the arrangements were too long, or too complex, or otherwise not appropriate. From that time until the early years of the new century, I did not write guitar music for publication.

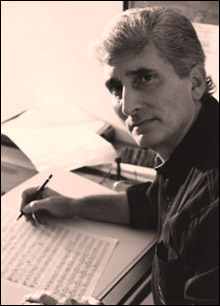

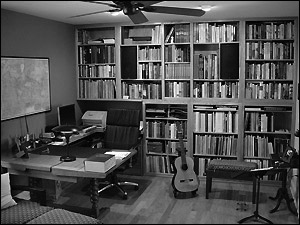

Along the way, I had gradually devoted more attention to composing for symphonic ensembles, and less to writing for solo guitar. Difficult as it is for a new orchestral composition to find its way onto a symphony orchestra's program, I have been extremely fortunate to have thoughtful and auspicious performances of my orchestral pieces. Writing for orchestra is a thrilling experience. Aside from the artistic catharsis which composition fosters, both the process of conception in terms of orchestral colors and the exercise of writing it out, are effective ways for a musician to maintain and enhance important skills. For a guitarist though, writing for guitar is a more personal matter. The instrument is always at an arm's reach and, as soon as the writing is finished, the piece can be realized. In the years since I last wrote for publication, I was able to write for the guitar as I pleased, without external prescriptions.

Along the way, I had gradually devoted more attention to composing for symphonic ensembles, and less to writing for solo guitar. Difficult as it is for a new orchestral composition to find its way onto a symphony orchestra's program, I have been extremely fortunate to have thoughtful and auspicious performances of my orchestral pieces. Writing for orchestra is a thrilling experience. Aside from the artistic catharsis which composition fosters, both the process of conception in terms of orchestral colors and the exercise of writing it out, are effective ways for a musician to maintain and enhance important skills. For a guitarist though, writing for guitar is a more personal matter. The instrument is always at an arm's reach and, as soon as the writing is finished, the piece can be realized. In the years since I last wrote for publication, I was able to write for the guitar as I pleased, without external prescriptions.

In the course of time, I have been gratified to receive many letters from guitarists in North America, South America, Europe, Asia and Australia, who knew my work of years ago and found it useful. Many have asked whether I had any plans to publish again. More recently, the letters have come by way of email. It was some time before I realized that this (relatively new) mode of communication offered the possibility of making my work available without restrictions. At that juncture, a fine web-site designer became available to me and, with him, the company that would make an adequate site possible.

This site was developed as a vessel of personal and professional information. www.MusicforEnsemble.com on the other hand, was designed to present and offer my orchestral, chamber and solo arrangements and compositions. At this time, that site is my current project and the last of all possibilities I could have imagined many years ago when my career began. I remember, with some nostalgia, the time when engraving music was still done with hammer and dies on a copper plate.  At the publishing company we used to call those guys "the Flintstones", in allusion to their tools; their work was beautiful. I am now rewarded by the possibilities and new experiences the current technology brings. While something less than proficient on matters of computers and their applications, I am fortunate to have the advice and technical support of very bright people. We have plans to continue to expand our current catalog and hope to always offer interesting and well finished publications of lasting value to our patrons. I am grateful for all the opportunities and rewarded by the work I have been able to do.

At the publishing company we used to call those guys "the Flintstones", in allusion to their tools; their work was beautiful. I am now rewarded by the possibilities and new experiences the current technology brings. While something less than proficient on matters of computers and their applications, I am fortunate to have the advice and technical support of very bright people. We have plans to continue to expand our current catalog and hope to always offer interesting and well finished publications of lasting value to our patrons. I am grateful for all the opportunities and rewarded by the work I have been able to do.